This article first appeared in the Cape town Family History Society Newsletter, December 2021.

As one goes through Baptism, Marriage and Burial registers one comes across names that are connected with some other historical event than the one you were looking for. In between the SMITHs, the JONESs and other common names suddenly a name pops up and with it, some interesting connections.

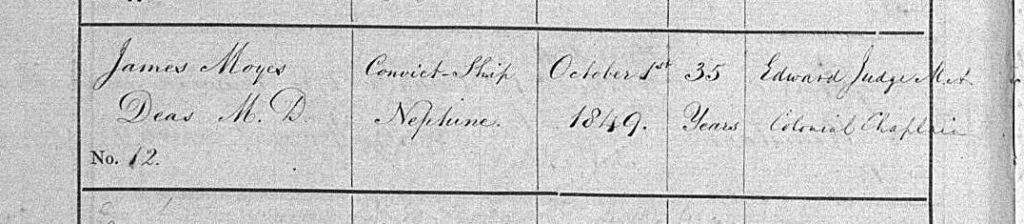

The other day I was paging through the 1849-1937 St Francis, Simon’s Town Burial Register looking for a specific name when my eye was distracted by this entry:

James Moyes Deas M.D. Convict Ship Neptune October 1st 1849 35 years The Rev Edward Judge, MA Colonial Chaplain

This entry has at least four things that perhaps deserve more attention. 1

- Convict Ship Neptune

The first thing that did attract my attention was ‘Convict Ship Neptune’. I first came across this ship when I was at school over 50 years ago! We had an Afrikaans setwork book dealing with the attempt to land convicts at the Cape. My Afrikaans was appalling then, so besides the name ‘Neptune’, I remember nothing about the book! More recently I seem to remember someone talking at the Cape Town Family History Society (CTFHS) meeting about Sir Robert Stanford who had supported the ‘Neptune’ by providing fresh produce for the feeding of the convicts (and crew) which the British government were hoping to disembark in the Cape Colony.

Once again, some questions arose in my mind. Never mind the story of the Neptune (I will deal with that below), I was curious why the British Government were trying make the Cape a penal colony? I found a fascinating doctoral thesis by John Marincowitz submitted to the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London in 1985. His thesis looked at labour and production in the rural areas of the Cape Colony, particularly the wheat growing region, in the 19th Century. His opening chapter tells of the growing tensions between ex-slaves who sought to reduce their dependency on farm wages and the farmers who sought measures to ensure they remained as wage-labourers (or as Dr Marincowitz, using Marxist terminology, called them ‘proletarianization of the ex-slaves’)2 This tension culminated in the years 1848 to 1853 when the Colony hovered on the brink of civil war.

The Need for Convict Labour at the Cape?

Many of the town-dwelling merchants such as John Bardwell Ebden, were keen that British labourers should be encouraged to come to the Cape. Most Farmer saw these as being too expensive to pay when compared to ‘the cheaper and more malleable’ black labourers. Some attempts were made by the Cape Legislative Council to have aided immigration from the UK. Esme Bull lists in the appendices of her book, Aided Immigration from Britain to South Africa: 1857-67, those who came under this initial scheme between 1848 and 1851.

Sir Harry Smith proposed to the British parliament that British labourers be imported to the Cape but the British Parliament changed ‘labourer’ to ‘convicts.’ This created an uproar at the Cape with a large number of objections from people across a wide spectrum. They thought a large number of criminals would create instability as the rural areas had few policemen. As Marincowitz puts it so succinctly ‘Employers at the Cape did not want convicts: they wanted labourers; in the mind of the British ruling class there was little distinction.’3 It turned out that the prisoners that were planned to be sent to the Cape were not common criminals or as Earl Grey said: ‘not the refuse of English gaols’4 but political offenders mainly from Ireland many of whom had risen up against the English landowners as a result of the potato famine. Being political offenders rather than common criminal didn’t help to change attitudes at the Cape. The Cape had experienced two politically active Irish seamen, James Hooper and Michael Kelly, together with the slave Louis from Mauritius and Muslim slave Abraham van die Kaap who had fermented a protest march of slaves in Cape Town in 1808.

But it wasn’t just the labour shortage that led to convicts being sent to the Cape. Magistrates in the Ireland were sentencing more and more people to be transported. In 1846 six hundred and ninety-seven offenders had been transported but two years later in 1848 the number had risen to two thousand seven hundred and thirty-three. As Lord Grey told parliament: ‘the parishes throw their burden on the counties, the counties upon the nation and the nation is forging schemes to throw it upon the colonies’.5

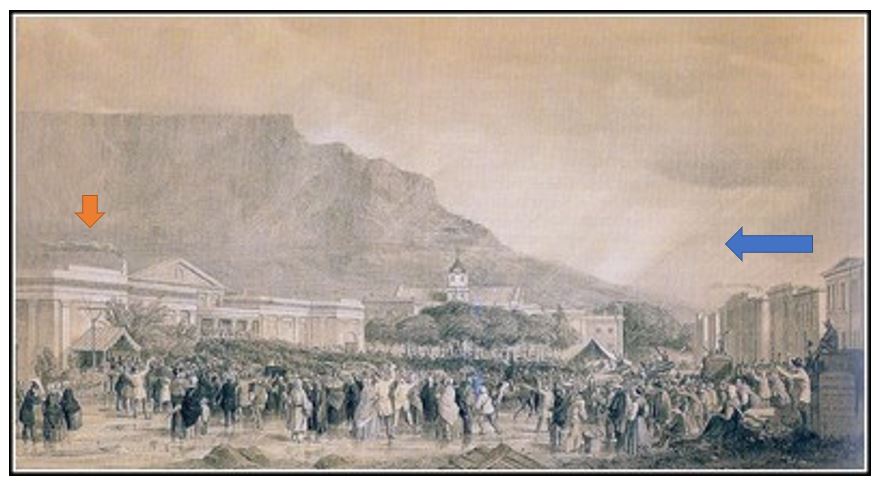

Thus, the Neptune filled with 282 prisoners6 and 55 crew was ‘throw upon the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope’. She arrived in Simon’s Bay on 19 Sep 1849.

Even before it arrived at the Cape a mass meeting was held on the 5 Apr 1849 where a crowd of 5,000 formed the Anti-Convict League. The League was headed by John Bardwell Ebden, Hamilton Ross, Hercules C. Jarvis, H. E. Rutherford and Dr. James Adamson, all well-known settlers at the Cape. They launched a vigorous campaign to boycott supplying the ship or dealings with any of the convicts that might be landed. A large number of people in the Colony signed in agreement. However, there were a few local businessmen who did not sign and they supplied the ship with provisions while it waited for a total of five months in Simon’s Bay. These few who had not signed the petition found that local shops would not serve them and they could buy no foodstuffs for themselves.

Among these people was Robert Stanford – more about him below. A brief search for him on Google produced a few Irish sites who praise this Irish-born man for his humanitarian support of the convicts and crew of the Neptune by selling produce to the ship. Stanford was later awarded a knighthood, by the same British government who had arrested those Irishmen on the Neptune for fighting for their political freedom, so was it not as a support of the Irish independence struggle that Stanford supported the Neptune. I also found a history of the Neptune crisis on a wine estate website. This wine estate is on the estate, Kleinrivier Valley which was the estate originally owned by Robert Stanford. On their website is an interesting comment:‘…the colonists believed [those on board the Neptune] to be convicts and would not stand for this and declared that anyone associated with the ship or its occupants would no longer be supplied with any provisions or services. Thus, when the “convict” ship Neptune arrived its passengers, who were ordinary Irish men, were kept at sea for five months.’

This statement opens up some interesting ethical discussion points. Firstly, two things needed to confirmed. Were all the convicts Irish and secondly, can they be called ‘ordinary Irish men’?

The Australian website https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/neptune/1849 lists by the name all those who were on the Neptune off Simon’s Town and later sent on to Van Diemen’s Land. It lists where the people were convicted. This shows that of the 306 passengers or convicts, 46 were convicted in English, Welsh and Scottish courts as well as 9 military personnel convicted by Court Martial in such diverse places as Malta, Athlone, Barbados, Belfast Barracks, Gibraltar, Salford Barracks, and St Johns Newfoundland. Some of these (Athlone and Belfast Barracks perhaps) might have an Irish connection but certainly the majority of the forty-six people were convicted for criminal activity. There were 192 Irish ‘convicts’ many of whom had turned to crime because of the infamous ‘Great Potato Famine’ of 1848.7 André Morkel summarises the situation very well when he wrote on the Morkel family website:

In April 1849 the Privy Council in London decided to make the Cape Colony another convict settlement, similar to those in Australia. The third Earl Grey, Colonial Secretary, intended to send a special class of convicts to the Cape. They were Irish peasants who had been driven to crime ((My emphasis)) by the famine of 1845. They were also towards the end of their sentences and the idea was that they could obtain a ‘conditional pardon’ to settle as ‘free exiles’ at the Cape, provided they did not return to Ireland, England or Scotland. Earl Grey sent a letter to the Governor at the Cape asking to ascertain the feelings of the colonists regarding this special category of convicts. Due to a misunderstanding, the Neptune arrived unannounced before the sailing vessel with Grey’s letter landed at the Cape. The ship also had the famous Irish rebel and activist, John Mitchel on board. In his book, Jail Journal, Mitchel is eloquent and scathing about the treatment of the Irish and the transportation system.

Although one can sympathise with these Irish men who, through hunger, turned to crime but they were still arrested, tried, found guilty and sentenced for transportation as convicts.

One of the convicts transported on the Neptune was Michael Morton (Moreton on the list of convicts). His Australian descendants have written a short history of the Moreton family. Two brothers – John who had been transported earlier for an attempted assassination of Theophilus Roe 8 and Michael who had stolen a cow. The writers of the story suggested that many cow-stealers were given a short sentence but maybe Michael Moreton was hoping to join his brother in Van Dieman’s Land. Perhaps at the trial, the judge passed a harsh sentence because of Michael’s brother, John Morton’s connection to the Young Irelanders protest group. However, to call the people onboard the Neptune, ‘ordinary Irish men’ is, I think, stretching it a bit.

Sir Robert Stanford

Stanford originally supported the blockade of the Neptune but he finally relented to a plea from the government at the Cape, after a visit from the Derry-born Attorney-General, William Porter, to offer assistance. This, Stanford believed, would bring “timely assistance” and thus “open rebellion and civil war would be averted”. He was given the option of providing supplies or a state of martial law would be declared and the provisions would be taken by force. Duty-bound to comply, Stanford complied with the Governor’s request but was not seen as a hero in the eyes of the colonists. They regarded his actions as treason and ostracised Stanford and his whole family. Stanford and others who provided help were persecuted, banks refused to do business with them, their children were expelled from school and the servants left their farms. The persecutions continued even when Stanford’s youngest daughter fell ill and the doctor refused to even see her, let alone treat her. Tragically this resulted in her death. Desperate, Robert Stanford travelled to England to plead his case and ask for compensation for his losses. His plea resulted in him being knighted and he received £5,000 for his return to the Cape. Upon his arrival, he discovered his farms were in ruins and had been stripped, some even sold by the people he left in charge. His farm Kleine Riviers Valley was sold for a pittance to a Phillipus de Bruyn at auction. Reduced to poverty and defeated by life, Sir Robert Stanford returned to England, where he passed away in Manchester at the age of 70. On 30 September 1857, De Bruyn sold the first plot of the new village he decided to call Stanford.

By February 1850, Earl Grey realised a resolution could not be reached and he ordered that the Neptune continue on its voyage to Van Dieman’s Land (the name used by Europeans for the island that was renamed Tasmania, in 1856). In London, Lord Adderley pleaded the Cape Colony’s case and this led to the Imperial Government changing their mind and the Neptune was sent on its way to Tasmania. In gratitude, the main street of Cape Town, Heerengracht, was renamed Adderley Street.

In his memoir (later published as Jail Journal) John Mitchel wryly remarked about the stand-off in Cape Town: “So the contest is over, and the colonists may now proceed about their peaceful business. Long may they sleep in peace without bolt or lock on their hospitable doors!”9

One of the good things to come out of this event was that the British Parliament asked the governor, Sir Harry Smith, to report whether the Cape was ready for self-government. This was granted in 1854 with a liberal constitution.

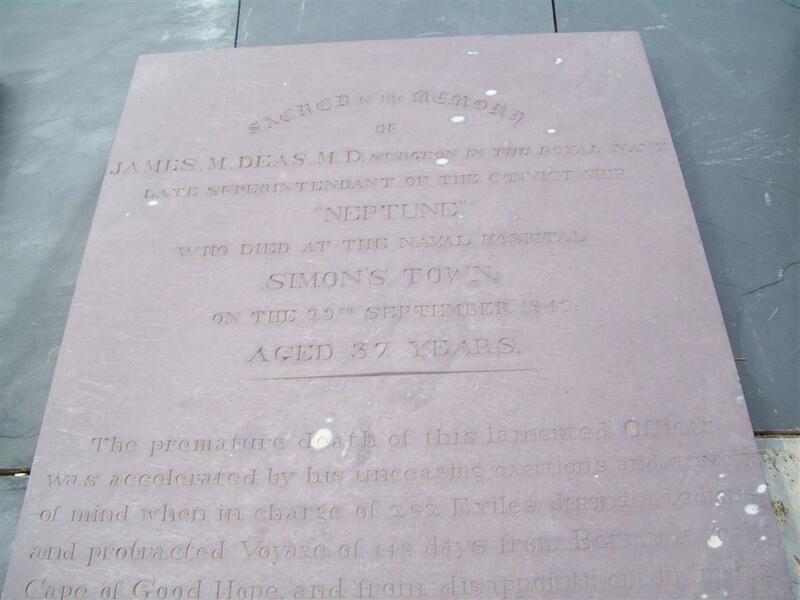

James Moyes Deas M.D

The medical officer on the Neptune was the Royal Navy surgeon, Dr James Moyes Deas. He died 29 Sep 1849 at the Naval Hospital, Simon’s Town and was buried 1 Oct 1849 in the old Seaforth Cemetery. His age in the burial register is given as 35 years but on the tombstone in the Seaforth Cemetery it states 37 and this matches his Baptism record. An Ancestry online family tree has a comment next to his death:

Surgeon, RN. He was the surgeon on board the Convict Ship, Neptune, which was prevented from docking in Simon’s Town due to protest. The stress of the situation led to his having what appears to have been a “nervous reaction”, which led to his death.[2]

The source for this entry in the online family tree was the Royal Naval Officers Service Index which states only his name and appointment date to the Neptune as 16 Jan 1849. No mention is made of his death or “nervous reaction” in this record. The Neptune had arrived in Simon’s Bay on 19 Sep 1849 and within ten days Dr Deas had died.

James Moyes Deas was born on 11 Nov 1811 in Falkland Parish, Fifeshire where he was baptised on 16 Nov 1811. His parents were Francis Deas and Margaret born Moyes. James’s father, Francis Deas was Provost[3] of Falkland. His mother Margaret Moyes had connections with slave-owning Moyes family from The Hermitage, St Elizabeth, Jamaica, a coffee plantation and they were paid compensation after the emancipation of slaves.

James Moyes Deas had two brothers who appear in the Oxford National Dictionary of Biography. They are Sir George Deas (Lord Deas) 1804-1887 who was a judge, and Sir David Deas (1807-1877) who, like his brother James, was a Naval Surgeon. He fought in the Crimea War and was awarded a knight hood. Sir David Deas had gone to Edinburgh High School and trained as a doctor at the University of Edinburgh, so probably this was the same route James Moyes Deas took as well.

1 October 1849 Burial

James Moyes Deas was buried in the Seaforth Cemetery originally called the ‘Old Burial Ground’ after the new cemetery at Dido Valley was opened. The cemetery was established in 1813. For more info on its history and who was buried there see http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/visiting-historic-simons-town-old-burying-ground

The Naval part of the cemetery is well looked after as this falls under the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The eGGSA database of cemeteries has 211 names of persons buried there. The Dutch Reformed section was where many Boer Prisoner-of-War who died in the two camps at Simon’s Town were buried. Besides the individual graves there are numerous monuments and memorials to sailors who died at sea or while on patrol up and down the African coast while their ships were based at Simon’s Town

The Colonial Chaplain Rev Canon Edward (Conduitt) Judge, MA.

Bishop Gray called for a Synod to establish a Church of the Province of South Africa. In the eyes of the courts this was seen to be a church separate from the Church of England. This caused much dissent and schism. In 1861 St Francis, Simon’s Town representatives attended the Synod and joined the Church of the Province of South Africa. However, as it can be seen, the priest at St Francis continued to sign the register as ‘Colonial Chaplain’. This seemed to continue right until the 1890s. It would be interesting to know when the Cape Government ceased to pay Colonial Chaplains. Was the continued use of the title by priests a protest against Gray or merely habit they failed to stop?

The Rev Edward Judge

Born: London in 1801, the son of Joseph Judge, of the London Custom House.

Educated: St Paul’s, London; and at Gonville and Caius (admitted pensioner, 12 January 1820), and Trinity (migrated, 11 May 1820; matriculated, Michaelmas 1820; Scholar, 1823; BA, 1824; MA, 1825) Colleges, Cambridge.

Ordained: Deacon, 7 November 1824, by the Bishop of Ely for the Bishop of London, and Priest, in the Reformed Church, Cape Town on 9 September 1832, by the Bishop of Calcutta, the Rt. Revd Daniel Wilson, under special commission for the Bishop of London. (One of the first two Anglican priests ever ordained in Africa.)

Career: Arrived at the Cape, 2 May 1825.

Committee member, South African Infirmary Fund, and the Philanthropic Society for aiding deserving slaves and slave children to purchase their freedom (established 1828).

Professor of Classics, South African College, 1829-1830. Resigned from the South African College “in consequence of a resolution of the Council not to allow religious instruction”, August 1830.

Founded his own private grammar school in Cape Town, 1830.

Provisional Chaplain of Wynberg (1832-1834);

Colonial Chaplain of Rondebosch (1834-1840);

Colonial Chaplain of Simon’s Town (1840-1874), all in Cape Colony.

Priest-in-charge (later Rector) of St. Frances’, Simon’s Town (licensed by the Bishop, the Rt. Revd Robert Gray, 2 August 1848; served until 1874), and Canon of St. George’s Cathedral (1852-1875), both in the diocese of Cape Town.

Fell ill, May 1852, and sailed for England on leave, June, 1852, returning to the Cape in November 1853. Attended the first synod of the diocese of Cape Town, January 1857.

Died: Simon’s Town, on 6 January 1875.“His history is written in the hearts of many and many a Cape family. What the present great educational enthusiasm of the Cape owes to him it might be hard to apportion exactly, but we are inclined to call him ‘the Alfred’ of it. At all events, with that calm, quiet resolution so characteristic of him, he strove hard to give to the Cape boys of nearly fifty years ago the same refined and liberal education which he had received and so highly prized himself. His sweet temper, sportive humour, never failed him to the end” (The Cape Argus, quoted in The Church News).

CONCLUSION

A chance spotting of ‘Convict ship, Neptune’ in the burial register of the parish of St Francis Simon’s Town resulted in further research into the area of labour shortage at the Cape in 1840s; the attempt by the Colonial Secretary and the British parliament to make the Cape Colony a penal settlement; the varied response of the people at the Cape; the death of the medical officer or surgeon on board the Neptune and his family, and a brief look at the Rev Edward Judge, the Colonial Chaplain. This research has opened a desire in me to visit the Seaforth Cemetery again (last I visited it was in 1970s) as well as a huge growth in and respect for the people of the Cape in the 1840s and 1850s.

Source Bibliography

- Australian Convict arrivals. The Neptune 1849 https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/neptune/1849

- Day, E. Hermitage. Robert Gray: First Bishop of Cape Town. London: SPCK, 1930. found at http://anglicanhistory.org/africa/day_gray.html

- de Villiers, Andries William. Messengers, Watchmen and Stewards. Johannesburg: Historical Papers, The Library, University of Witwatersrand, 1998.

- Deas Family Online found at https://www.ancestry.co.uk/familytree/person/tree/151739409/person/372009933790/facts?_phsrc=jBv22&_phstart=successSource

- Gravestone Database eGGSA Database at https://www.graves-at-eggsa.org/librarySearch/searchGraves.htm

- The Irish Times: Why the famine Irish didn’t emigrate to South Africa https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/abroad/why-the-famine-irish-didn-t-emigrate-to-south-africa-1.3397555

- Morkel, Andre. Breaking the Pledge: The Family Ostracised. Revised August 2018. Published on the family.morkel.net website. https://family.morkel.net/wp-content/uploads/Neptune-Ostracised-1.pdf

- Royal Commonwealth Society. Cape Town Anti-Convict Petition, 1849. found at https://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/rcs

- Royal Navy Records: Dr James Deas. The National Archives at https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D7609101

- Scotland’s People Birth Marriage and Death Records. https://www.scotlandspeople.gov.uk/

- Simon’s Town Old Graveyard http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/visiting-historic-simons-town-old-burying-ground

- St Francis, Simon’s town: Burial Register http://www.familysearch.org

- A. Convict Ship Neptune B. Dr Deas himself C. Date of Death – Comparison between date of death and date of burial and why Neptune still in Simon’s Bay? D. Colonial Chaplain. [↩]

- John Marincowitz, Rural Production and Labour in the Western Cape, 1838 to 1888, With Special Reference to the Wheat Growing Districts. Unpublished Doctoral Thesis SOAS, University of London, 1985 quote from the Abstract. [↩]

- Marincowitz, p70 [↩]

- Marincowitz, p75 [↩]

- Marincowitz, p76 [↩]

- There is some variance in the numbers found at different websites. An Australia convict site lists 306 ‘passengers’ https://convictrecords.com.au/ships/neptune/1849. However, The Irish Times says 18 died at sea before arriving at the Cape [↩]

- André Morkel, Breaking the Pledge: The Family Ostracised. Revised August 2018. Published on the family.morkel.net website. https://family.morkel.net/wp-content/uploads/Neptune-Ostracised-1.pdf [↩]

- Theophilus Roe was a wealthy Anglo-Irish property owner [↩]

- https://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/abroad/why-the-famine-irish-didn-t-emigrate-to-south-africa-1.3397555 [↩]