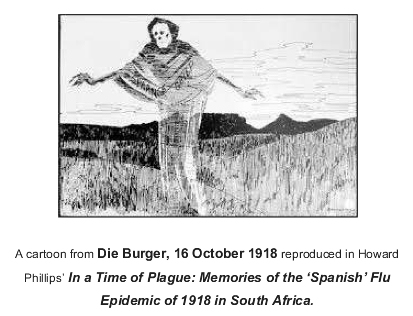

The Burial Register of St Paul’s, Rondebosch for the year 1918 makes fascinating reading. Particualrly interesting is the period in October when the second wave of infections of the so-called Spanish Flu caused havoc in South Africa.

Although Apartheid legislation – especially the Group Areas Act (GAA), was not yet legally part of the South African way of life, society was most definitely divided, usually economically but, in truth, that meant racially because of the poverty among the people of colour. In Cape Town that meant the so-called ‘Coloured’ or Mixed Race population. These people were descended from various sources. They were descendants of the original population from around the Western Cape (San and Khoi people), the descendants of slaves brought to the Cape during the previous two centuries, and the descendants of mixed-race marriages. Having traditionally held lowly paid jobs and without any opportunity to improve themselves through education, the ‘Coloured’ people were frequently forced to live on the edges of the towns and cities. In attempts to improve the health and sanitation of the city, they had been moved to suburbs well away from the White colonial settlers.

Rondebosch in 1918 (in fact up to the introduction of the GAA in 1950 and forced removals in the 1960s), was a very mixed community with pockets of large houses of the wealthy property owners and small cottages where the servants lived.

The Parish of St Paul’s, Rondebosch at that time consisted of the Parish Church (St Paul’s on the Main Road to Simon’s Town) and four Chapelries. The chapels were St Thomas’s near Rondebosch Common, St Mark’s in Athlone which was called at various times, West London or Milner, St George’s in Rylands (later the church moved to what is now known as Silvertown) and St James, Black River (the area immediately below where Red Cross Children’s Hospital is now).

The Parish graveyard at St Paul’s had been shut in the 1880s and that at St Thomas in the early years of the 20th Century, however a piece of land had been donated near where Garlandale High School is today and this became known as Black River Cemetery and in the burial Register the initials “B.C.” next to an entry meant that the burial had occurred at Black River Cemetery. Because of where it was situated, most (if not all) of the burials at Black River Cemetery were of ‘Coloured’ people and usually members of St Paul’s Parish worshipping at the Chapelries. Other burials were at Maitland Cemetery. In 1918 there was not crematorium in Cape Town.

A careful examination of the burial register shows a strange phenomenon of two batches of burial entries for October 1918. Instead of each entry being in date order, the first batch covered the period from 7 Oct to 24 Oct 1918 and entered by the Rector, the Rev. John Brooke. No racial classification was required in the burial and the baptism registers. This was only required in the Marriage Register where the minister became a quasi-government official carrying out the marriage for the state. Other Civil Registrations (Births and Deaths) were done through official government channels so church records registers for these did not require racial classifications. Therefore it is hard to know which of the burials done in this first batch of entries were of White people and which were ‘Coloured’ people who lived near the Parish Church in what would later (in the 1960s) be a White area of Rondebosch.

1918 Spanish Flu Epidemic in Rondebosch Parish

| First Batch of Burials | Second Batch of Burials | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of Burials | 28 | 153 |

| < 15 years of age | 3 | 47 |

| Between 15 and 45 years of age | 22 | 95 |

| > 45 years of age | 3 | 11 |

| Average age | 29y 4m | 23y 6m |

| Males | 17 | 80 |

| Females | 11 | 73 |

| Days in period when funerals held | 13 of 17 days | 16 of 17 days |

| Average number of funerals per day | 2 | 9 |

| Largest number of funerals per day | 6 on 10 Oct 6 on 11 Oct | 18 on 12 Oct 20 on 13 Oct 16 on 14 Oct |

The Second Batch of entries in the Parish Burial Register were from 5 Oct to 21 Oct 1918. These burials were carried out by the curate, the Rev. T. L. Floyd, who had responsibility for St Marks, St George’s and St James. (St Thomas’s fell under the Rector, whose rectory was right next door.)

Conclusion

Over five times more ‘Coloured’ people living in West London (Athlone) died and were buried in the first three weeks of October 1918.

Of the total of 178 people, 50 were younger than 15 years – 47 of whom came from West London. What must be borne in mind is that poverty with malnutrition and poor housing made the young ‘Coloured’ children more vulnerable to disease. Of the 178 people, only 14 were older than 45 years. Seven percent of West London deaths in the older category and 10 percent from the Parish Church (most probably White).

The balance (117 people) were in the working age of 15 -45 years. In the West London (‘Coloured’) community this made 62% of those buried. In White or Parish Church area this made up 78% of those buried.

As far as Gender breakdown goes, in the West London there was hardly any difference, which is interesting to think about (male 80, female 73, ratio 1.09). In the parish church the number of male to female death is more stark (male 17, female 11, ratio 1.54). Researchers say that younger males in the working age group (15y to 45y), because they met others at work, were more susceptible to being infected. This explains why, in the White community, more males than females succumbed. All I can suggestion at the similar number of deaths in West London is that poverty malnutrition and over-crowded housing has no gender-awareness.

Throughout the COVID19 pandemic we were told how the elderly were more vulnerable, which is different the Spanish Flu of 1918.