Recently a number of people who knew that I was researching the St Paul’s Graveyard, Rondebosch sent me a Facebook or email message about the article on St Paul’s on The Heritage Portal by S. J. de Klerk.1 In the article de Klerk makes mention of the NIGHTINGALE grave and the fact that the gravestone mentions William, ‘who fell a victim to Delagoa Bay fever on his way to the Gold Fields and died at Geelhoutboom…aged 23 years.’ Purely by chance in the same week as I was told about this article, I was working on the NIGHTINGALE family’s history for my St Paul’s Graveyard Project vide www.thefamilyhistorian.co.za and click on St Paul’s Graveyard on the menu.

William himself is not buried at St Paul’s Graveyard but his brother Charles NIGHTINGALE is. They were sons of Joseph NIGHTINGALE who was a draftsman for ‘Her Majesty’s Ordinance Department of the War Office’. He was married three times and had a daughter in each of the first two marriages and six children with his third wife. His first wife died, his second, from what I’ve found, ended up in the Wandsworth Workhouse and in the list of those who died in the workhouse it shows her death on 23 August 1840. In the list next to her name and her age (29y) and date of death and it also says ‘Intoxication’. I find it strange that a man who is obviously doing well financially (he had servants in the Census records) should send his wife to the workhouse to die but unfortunately the mere BMDs do not tell you the story behind the facts. The daughter from this second marriage married an engineer and like her step sisters and brothers came to the Cape.

I am not sure if Joseph’s children all left for the Cape at the same time. All children but William appear at home with mother and father in Surrey in the 1871 Census. Charles must have left within the next year or two because he died ‘suddenly’ in Kalk Bay in January 1873 and his death notice was filled in by younger brother Walter Maxwell NIGHTINGALE and the gravestone commemorates William NIGHTINGALE dying a year later (1874) ‘on his way to the goldfields…’

Where did William die?

As S. J. de Klerk points out in The Heritage Portal website article, Geelhoutboom is a farm in the Graskop area where gold was discovered. The actually diggings were called Mac-Mac. Today there is a waterfall still bearing that name in Mpumalanga. It is a two-stream waterfall, because of the early gold-diggers using explosives to get to the gold and thus divided the stream.

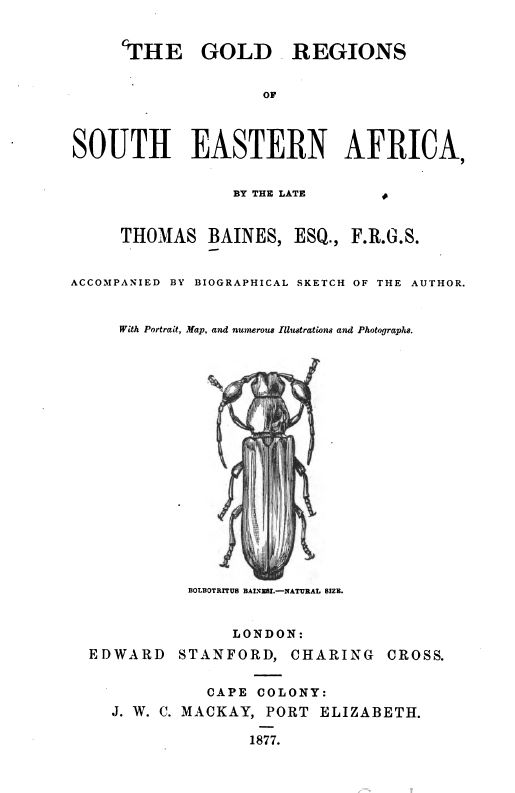

For gold-diggers from overseas or the Cape Colony and Natal, it was a long trek to get from the coastal areas to the goldfields by going across land. Thomas Baines, writing in his book The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa tells of the attempt to get to the fields via Delagoa Bay in Mozambique or Portuguese East Africa.

He wrote: A small iron steamer, the “Adonis,” had been brought from Europe and put together in Port Natal, and by the close of 1873 was fit for sea. Several persons took passage in her for Delagoa Bay, with the view of shortening the land journey, but the exposure to fever in the rains then prevalent, the detention and difficulty of procuring native carriers in Delagoa Bay, the entire absence of accommodation and consequent hardships, privations, and exposure, during a pedestrian journey of 178 miles, during which two large and several small rivers must be crossed, far more than countervailed the 240 miles saved in the distance. ((Thomas Baines, The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa. (Port Elizabeth: J.W.C.Mackay, 1877)page 148 also re-published in 1968 by the Rhodesiana reprint library, v. 1 ))

William NIGHTINGALE appears to be one of those who were infected by the fevers and hardships that Thomas Baines is talking about. Baines continued:

A letter from Pilgrim’s Rest, dated Feb. 16, 1874, records the death of three persons who had arrived, via Delagoa Bay, and states that hardly one had been exempted from attacks of fever; while many narrowly escaped with their lives, and were compelled to abstain from work till the bracing air of the elevated regions should restore their health. The first who died at McMc was William Nye Nightingale, aged twenty-six or twenty-seven, believed to have come from Durban; next, Thompson, aged twenty-seven or twenty-eight, formerly connected with a brewery in Cape Town. The third victim was named Stewart, aged about forty-seven. He was supposed to have come from Algoa Bay, was formerly an engineer in the service of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Company, was a widower, and had left a daughter. The writer considerately gives these particulars to facilitate the identification of the unfortunate victims to a deadly climate, and adds that every attention was shown them during their illness by the ladies of Mr. MacLachlan’s family, and they had such medical assistance as could be obtained on the fields. (( Baines, Gold Region ))

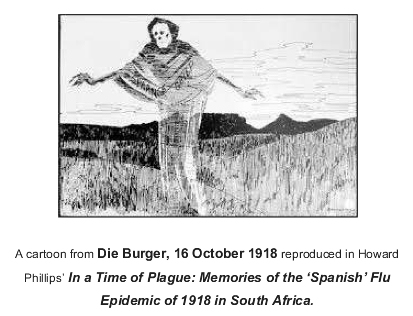

Delagoa Bay Fever

But what actually was Delagoa Bay Fever that William NIGHTINGALE is supposed to have died from? Most websites will tell you that it is Enteric Fever (Typhoid) or Malaria. I got this information when I googled it and found a digitised booklet by a Dr J.A. Simeons who had developed certain medications to fight this disease.

The booklet was published by B G. Lennon & Co. of Port Elizabeth. Lennon’s were a well-known pharmaceutical company and the inside cover of this tract tells the reader that

The medicines referred to in this Book are manufactured solely by B. G. LENNON & Co., and none are genuine unless bearing their name and address. The cost of a complete Medicine Chest is 50/nett each. Postage extra. (( J. A Simeon, Advice and Instructions for the prevention and cure of fever, which is prevalent in the Low Districts of the Transvaal, in Delagoa Bay, and East Africa. (Port Elizabeth: B. G. Lennon, 1890) p2 ))

Then there is a list of the ten different pills, mixtures, tinctures and powders with only Epsom Salts being given a name and not a number. The tract also had positive ‘reviews’ of the efficaciousness from numerous doctors and hospitals in the Eastern Transvaal. I must admit I felt it a bit like a classical quackery tract especially after I read the opening paragraph of this tract:

The poisonous substance giving rise to malarial fever is produced by putrefaction and decomposition of the decayed vegetable matter; the decomposed matter gives out an invisible poisonous substance called malaria, which, mixing with the air, gets into the human system through the lungs…. When a person breathes such a poisonous air and his blood becomes impregnated with malaria, he gets fever. Usually he receives premonitory warnings of the coming attack of fever one or two days before he is seized with it, for he feels a sense of weariness or fatigue on exertion, a disinclination for work, a want; of vigour and of cheerfulness, headache, pains in the body, want of appetite, disturbed sleep, and a general feeling of being out of sorts. The symptoms are observed more in new-comers in malarial districts, and in persons who are about to suffer for the first time from an attack of fever.2

However, that made me ask when was it realised that the mosquitoes were the spreaders of malaria. I discovered that this discovery only came in 1897 by Dr (later Sir) Ronald Ross whose story is also fascinating.

Sir Ronald Ross was born in Almora, India in 1857. At the age of eight, like most children of the Raj, he was sent to England to be educated. During these early years he developed interests in poetry, literature, music, and mathematics, all of which he continued to engage in for the rest of his life.

Although he had deep desire to study medicine, at the age of 17 he submitted to his father’s wish to see him enter the Indian Medical Service. He began his medical studies at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital Medical College, London in 1874 and sat the examinations for the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1879. He took the post of ship surgeon on a transatlantic steamship while studying for, and gaining the Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries, which allowed him to enter the Indian Medical Service in 1881, where he held temporary appointments in Madras, Burma, and the Andaman Islands. During a year’s leave, from June 1888 to May 1889, he developed his scientific interests and studied for the Diploma in Public Health from the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons in England and took a course in bacteriology under Professor E. E. Klein.

In 1892 he became interested in malaria and, having originally doubted the parasites’ existence, became an enthusiastic convert to the belief that malaria parasites were in the blood stream when this was demonstrated to him by Patrick Manson during a period of home leave in 1894. Sir Patrick Manson is considered by many to be the father of tropical medicine. He was the first person to demonstrate, in 1878, that a parasite that causes human disease could infect a mosquito—in this case, the filarial worm that causes elephantiasis. He was the founder of the London School of Tropical Medicine.

On Ross’s return to India in 1895, he began his quest to prove the hypothesis of Alphonse Laveran and Manson that mosquitoes were connected with the propagation of malaria, and regularly corresponded with Manson on his findings. However, his progress was hampered by the Indian Medical Service, which ordered him from Madras to a malaria-free environment in Rajputana. Ross threatened to resign but, following representations on his behalf by Manson, the Indian Government put him on special duty for a year to investigate malaria and kala azar (visceral leishmaniasis).

On 20 August 1897, in Secunderabad, Ross made his landmark discovery. While dissecting the stomach tissue of an anopheline mosquito fed four days previously on a malarious patient, he found the malaria parasite and went on to prove the role of Anopheles mosquitoes in the transmission of malaria parasites in humans.

While Ross is remembered for his malaria work, this remarkable man was also a mathematician, epidemiologist, sanitarian, editor, novelist, dramatist, poet, amateur musician, composer, and artist. He died, after a long illness, at the Ross Institute on 16 September 1932.3

“…With tears and toiling breath,

I find thy cunning seeds,

O million-murdering Death.”

(This is a fragment of a poem by Ronald Ross, written in August 1897, following his discovery of malaria parasites in anopheline mosquitoes fed on malaria-infected patients)

So maybe I’m being too harsh on Dr A J Simeon especially as he had good medical school qualifications. He was Doctor in Medicine and Surgery at the University of Brussels, had the Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of London, the Licentiate of the University of Bombay, and qualified in Sanitary Science and Public Health in the University of Durham.

What about the rest of the NIGHTINGALE family?

Louisa, Joseph’s daughter from his first marriage married George GARWOOD, a horse dealer. They had four children before Louisa died in 1857.

Emily daughter of second wife Emily Kilbourn NIGHTIGALE and Joseph, married an engineer and had five children who seemed to have come to South Africa at some point. One daughter died as an unmarried Art Teacher and another married into the HARE family – well-known in Rondebosch and St Paul’s.

Joseph, with his third wife Julia NELTHORPE had seven children and all of them seem to spend at least some time in South Africa, if not living (and dying) here. Laura (b1948-d1927) had an estate file in Cape Town although dying unmarried in Exmouth, Devon. Charles and Williams died as described on the grave at St Paul’s, Rondebosch. The third son, Arthur was manager of Cape of Good Hope Bank in East London when he decided to head off to the same goldfields that took his brother’s life. Arthur NIGHTINGALE died 23 March 1884 ‘between Delagoa Bay and Lydenburg’ as his death notice puts it. He was unmarried. His Death notice was only filed nearly a year later in February 1885. It was completed by sister Florence Julia NIGHTINGALE who later married John DALLAMORE and had three children.

The only son of Joseph and Julia to marry and have off-spring, was Walter Maxwell NIGHTINGALE (b1855-d1921). After farming in Natal, he went to Kenya. One daughter married a HULETT, one son farmed in Kenya after his father’s death and the youngest daughter married and moved to the USA. Walter Maxwell NIGHTINGALE was awarded a MBE. These initial appear on many of his records but I am not sure whether it was for his war service in East Africa during WW1 (he must have been over 60 years old) or for colonial service in Kenya – his name does not appear in my searches of MBE recipients in London Gazettes where the awards would appear.

That only leaves the youngest child, Frederick Joseph NIGHTINGALE which I managed to find in Alexis Creek, British Columbia, Canada. When he died in 1897, his probate was carried out in London and he left £45 to his sister Laura. I found him listed as a rancher in Chilcoten County but no mention in the Canadian Census of 1891.

Bibliography

Books

- Baines, Thomas. The Gold Regions of Eastern Southern Africa. Port Elizabeth: J. W. C. MacKay, 1877

- Simeon, J. A. Advice and Instructions for the prevention and cure of fever, which is prevalent in the Low Districts of the Transvaal, in Delagoa Bay, and East Africa. Port Elizabeth: B. G. Lennon, 1890

- The SA Archaeological Society, W. Cape Branch. Tombstones & Transcripts: St Paul’s, Rondebosch 19th Century Churchyard. Plumstead: My Shelf Publishing, 2007.

Websites

- Ancestry Website. Accessed 23 Oct 2020 http://www.Ancestry.co.uk

- De Klerk, J. S. The Heritage Portal: Visiting the Historic St Paul’s Church and Graveyard. Accessed 23 Oct 2020. http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/visiting-historic-st-pauls-anglican-church-and-churchyard

- Family Search Website. Accessed 23 Oct 2020. https://www.familysearch.org/en/

- Find my past Website. Accessed 23 Oct 2020. https://www.findmypast.co.uk/

- National Archives and Record Service Website. Accessed 23 Oct 2020. http://www.national.archives.gov.za/

- Ross and the Discovery that Mosquitoes Transmit Malaria Parasites on CDC website. Accessed 23 Oct 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/history/ross.html

- http://www.theheritageportal.co.za/article/visiting-historic-st-pauls-anglican-church-and-churchyard [↩]

- Simeon, Advice, 7 [↩]

- Abbreviated from https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/about/history/ross.html [↩]